The exit from Ethiopia was quick and without fuss. The entry into Sudan was the same, except a little more paperwork; immigration, customs for the bike, special separate permit for the bike for 15 Sudanese pounds, and then a security check which was only to write down info from my passport. The energy had shifted greatly after crossing the imaginary border line. The guy giving me the special permit (rather no permit just a fee), well I asked him if the banks would be closed for the next three days as one of the money changers had claimed, adding he was giving a very good rate for US dollars. Yeah I’ve heard that one before. But he didn’t understand and saw my Ethiopian Birr from our exchange and then he wanted me to follow him outside and I did, and then he left. So while waiting this young man I had seen earlier getting lunch for one of the workers asked me what I wanted and I said nothing, and he said do you want to exchange Birr for Pounds? Oh yeah, already wondering how this guy was going to shake me, but he didn’t, and he let me choose the rate which I got from the Belgiums back in Addis Ababa. And he just exchanged it for the rate I suggested from his own wallet and that was that. I said but aren’t you making any money on this? And he said no, I am doing this because you cannot change once you leave this border, and for me I can sell them later.So after the Security check I was on my way into Sudan, and just as I got up to third gear I felt my bike get all squirrely again and thought to myself, shit it’s the rear tyre. So I pulled over and she was dead flat.  Then I tried pumping the tyre up but it wouldn’t take any air so I knew I had a good puncture. My choices were to fix the tyre there on the side of the road, or walk the bike in first gear for 200 meters to the petrol station I had just passed. I decided on the later for if I run into a problem, at least there are people around to leave the bike and everything behind. The guy in charge who was very busy said sure no problem, so I parked the bike in front of the girl selling tea, took off all the luggage and removed the tyre. Then a young man came over to explain that he could take it to a Gomeria 1 km away, in Arabic I might add, but one can figure out any problem when one has a problem in any language. So I thought yeah, but he won’t have any money to pay the guy and etc. etc. so in the end I checked with the guy in charge and he said he would watch everything, including my tools lying on the ground beside the bike. So rather than patch myself, I thought it might be more efficient and faster if I walk back with the young man so I did. He carried the tyre and back in Gallabat it was fixed in thirty minutes, and upon returning with the tyre, I gave the young man a tip and he wanted only half of what I gave him, so I said he could keep the rest on principal, this is different I thought. After putting the tyre back on in front of the tea girl and the man who was sitting beside her when I had first arrived, I asked for a tea from the girl and then asked the man beside her how much it was and he said nothing, I paid for it. Then I learned he was an educated man, working the border as a private exporter. Later I offered the petrol guy a tip and he refused no problem he said. So I had another cup of tea with the man and girl and again he paid, so I tipped the girl, took their picture and headed off for Gedaref which I wanted to reach before dark which was coming up fast.

Then I tried pumping the tyre up but it wouldn’t take any air so I knew I had a good puncture. My choices were to fix the tyre there on the side of the road, or walk the bike in first gear for 200 meters to the petrol station I had just passed. I decided on the later for if I run into a problem, at least there are people around to leave the bike and everything behind. The guy in charge who was very busy said sure no problem, so I parked the bike in front of the girl selling tea, took off all the luggage and removed the tyre. Then a young man came over to explain that he could take it to a Gomeria 1 km away, in Arabic I might add, but one can figure out any problem when one has a problem in any language. So I thought yeah, but he won’t have any money to pay the guy and etc. etc. so in the end I checked with the guy in charge and he said he would watch everything, including my tools lying on the ground beside the bike. So rather than patch myself, I thought it might be more efficient and faster if I walk back with the young man so I did. He carried the tyre and back in Gallabat it was fixed in thirty minutes, and upon returning with the tyre, I gave the young man a tip and he wanted only half of what I gave him, so I said he could keep the rest on principal, this is different I thought. After putting the tyre back on in front of the tea girl and the man who was sitting beside her when I had first arrived, I asked for a tea from the girl and then asked the man beside her how much it was and he said nothing, I paid for it. Then I learned he was an educated man, working the border as a private exporter. Later I offered the petrol guy a tip and he refused no problem he said. So I had another cup of tea with the man and girl and again he paid, so I tipped the girl, took their picture and headed off for Gedaref which I wanted to reach before dark which was coming up fast. Twenty minutes into the ride, I was surrounded for a full 360 degrees of the same consistency of gray rain. I couldn’t even see clouds; it was all one big mass of consistent blah for as far as I could see in every direction. I couldn’t even see the shape of the sun or where it might be in the sky it was so thick. An hour into this and completely drenched, I came across yet another herder and his cattle, for this happens all day long. But this encounter was a little different. There were cows and goats on the left and right of me as I geared down heading toward them, with one cow in the middle of the road heading to the right side. So I went left, and then suddenly this cow jumped up on its hind legs and swung around 180 degrees to head for the left, so I went to the right and then this comedic cow changed to the right and then I hit the brakes, lightly squeezing the front and all rear brake and skidded for three seconds before realizing the cow was going to hit my right pannier, catapulting me to the left. But the comedian did the hind leg maneuver again, just missing my pannier. So I looked in my mirror at the covered yellow Sheppard, shook my head and kept on going, whew, what a day.

Twenty minutes into the ride, I was surrounded for a full 360 degrees of the same consistency of gray rain. I couldn’t even see clouds; it was all one big mass of consistent blah for as far as I could see in every direction. I couldn’t even see the shape of the sun or where it might be in the sky it was so thick. An hour into this and completely drenched, I came across yet another herder and his cattle, for this happens all day long. But this encounter was a little different. There were cows and goats on the left and right of me as I geared down heading toward them, with one cow in the middle of the road heading to the right side. So I went left, and then suddenly this cow jumped up on its hind legs and swung around 180 degrees to head for the left, so I went to the right and then this comedic cow changed to the right and then I hit the brakes, lightly squeezing the front and all rear brake and skidded for three seconds before realizing the cow was going to hit my right pannier, catapulting me to the left. But the comedian did the hind leg maneuver again, just missing my pannier. So I looked in my mirror at the covered yellow Sheppard, shook my head and kept on going, whew, what a day.  For another hour I rode in this rain, spooning the bike to keep my chest warm and to use my small windshield to block the painful rain needles hitting my face. My helmet shield is no good for this kind of rain for it’s too dark to see. Then I reached a fork in the road, but could clearly see I had reached Gedaraf. This man at the petrol station waved me over so I went into to confirm which way it might be to find a hotel, and to fuel up. Well this man was so excited and spoke very good English, asking me to take off my helmet for a picture, asking me for my email, asking me if it would be possible to come to Canada and marry a good Christian woman, asking me if I like whiskey, asking me if I believed in God, asking me if I would like to get something to eat ….. . After saying I was happy he was really happy, I said I had to go and get a room and dry myself and all my stuff and get something to eat. Then he shook my hand and then kissed it over and over and over until I pulled my hand away laughing saying I gotta go. He continued to hold me longer, grabbing my hand and kissing it again, until I had no choice but to start the bike, put her in gear and wave as I was riding off.

For another hour I rode in this rain, spooning the bike to keep my chest warm and to use my small windshield to block the painful rain needles hitting my face. My helmet shield is no good for this kind of rain for it’s too dark to see. Then I reached a fork in the road, but could clearly see I had reached Gedaraf. This man at the petrol station waved me over so I went into to confirm which way it might be to find a hotel, and to fuel up. Well this man was so excited and spoke very good English, asking me to take off my helmet for a picture, asking me for my email, asking me if it would be possible to come to Canada and marry a good Christian woman, asking me if I like whiskey, asking me if I believed in God, asking me if I would like to get something to eat ….. . After saying I was happy he was really happy, I said I had to go and get a room and dry myself and all my stuff and get something to eat. Then he shook my hand and then kissed it over and over and over until I pulled my hand away laughing saying I gotta go. He continued to hold me longer, grabbing my hand and kissing it again, until I had no choice but to start the bike, put her in gear and wave as I was riding off.  From his directions I found my way and when I reached the main intersection in town, I just looked at someone hiding from the rain, making the shape of a house with my hands and the sign for sleeping, he pointed just up the way and now I am here. I was again greeted kindly, and asked to be welcome over and over. The man in charge sent the housekeeper to get me some food, ¼ chicken, fresh vegetables and bread, and now I am satiated from another exciting day, scratching the zillion mosquito bites I acquired the first night in Gonder, even though I had a net over the bed, these ones were crafty, then again they were probably bed bugs for the bites lasted a long time. Even still though, in theory if they were mosquito bites they shouldn’t be carrying the malaria parasite for we were situated above 2000 meters.

From his directions I found my way and when I reached the main intersection in town, I just looked at someone hiding from the rain, making the shape of a house with my hands and the sign for sleeping, he pointed just up the way and now I am here. I was again greeted kindly, and asked to be welcome over and over. The man in charge sent the housekeeper to get me some food, ¼ chicken, fresh vegetables and bread, and now I am satiated from another exciting day, scratching the zillion mosquito bites I acquired the first night in Gonder, even though I had a net over the bed, these ones were crafty, then again they were probably bed bugs for the bites lasted a long time. Even still though, in theory if they were mosquito bites they shouldn’t be carrying the malaria parasite for we were situated above 2000 meters.  In the morning the manager of the hotel bought me and another man some tea, before I headed off for Khartoum.

In the morning the manager of the hotel bought me and another man some tea, before I headed off for Khartoum.

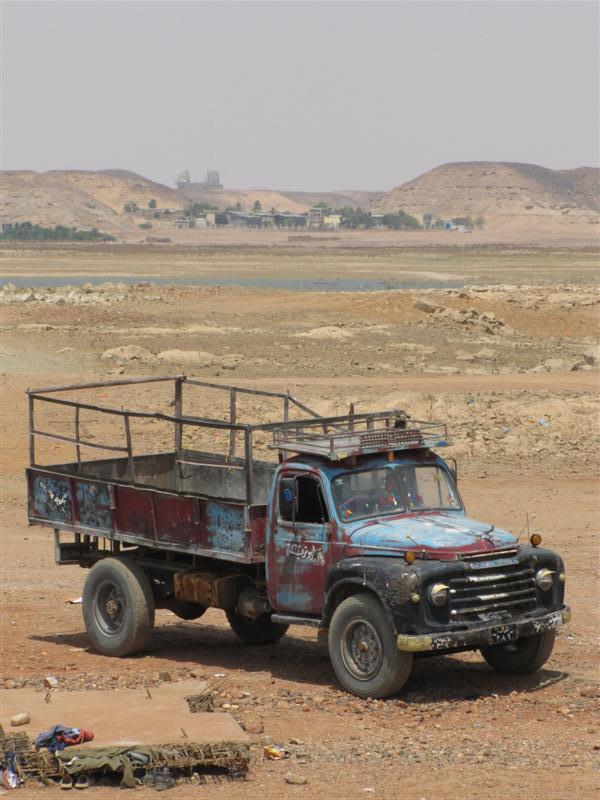

Later, the day became a hard ride, only because it became very hot, some 40 plus degrees. And the other factor was that it was a fast two lane highway, with each direction vying for first place. Either one gets caught in a line of slower moving vehicles, or one tries to reach some space by being as aggressive as the faster ones. I always opt for the second choice, for I figure if you’re in control, and not lined up with the others, there will be less vehicles passing you, which means you get to make the decisions instead of letting others make them for you. All in all it was an intense ride.

Later, the day became a hard ride, only because it became very hot, some 40 plus degrees. And the other factor was that it was a fast two lane highway, with each direction vying for first place. Either one gets caught in a line of slower moving vehicles, or one tries to reach some space by being as aggressive as the faster ones. I always opt for the second choice, for I figure if you’re in control, and not lined up with the others, there will be less vehicles passing you, which means you get to make the decisions instead of letting others make them for you. All in all it was an intense ride.  I had a nice lunch/breakfast on the side of the road with some friendly men, and some spicy beans and other ingredients before stocking up on water to continue the race. Below is the man who was preparing the food, and he proudly shared with me his French language.

I had a nice lunch/breakfast on the side of the road with some friendly men, and some spicy beans and other ingredients before stocking up on water to continue the race. Below is the man who was preparing the food, and he proudly shared with me his French language. Unfortunately, every time I got ahead of a long line of vehicles, I was stopped by the police checks, only to sit in the blazing sun while they checked my passport in a small office.

Unfortunately, every time I got ahead of a long line of vehicles, I was stopped by the police checks, only to sit in the blazing sun while they checked my passport in a small office.

Once in Khartoum I spent hours riding around looking for accommodation, trying to find some places in the guide book but never did. Incidentally I have no pictures of Khartoum, for my hands were busy. After losing my patience, my hydration level and my will to look further, I took a hotel that happened to be next to where I had stopped for information/tourism. Unfortunately the man didn’t speak enough English for me to get any good answers; like where do I register(once you have entered the border of Sudan you have three days to register yourself in Khartoum), and where is a hotel to park my bike safely? So I took this room for $60US, and the man said he could register me the following day if I filled out the form and gave him a passport photo, so I’ve decided to take up his offer after reading another rider’s blog about spending half the day trying to find the registration place, and then lining up for a long time etc ….. .Once in my room I washed some clothes in the shower, and had one myself. And then I went on-line to update my blog (free fast wireless). But for some reason I wasn’t able to load my page, every time it said ‘The connection was reset’, which is not unusual really. However after I was able to visit any other site quickly, even the larger ones that I sometimes have a problem with, I still wasn’t able to access my site. So I wrote my father and asked if he could see my site in the UK and he confirmed that he could. So I did some research and learned that Sudan, China and many other countries censor sites, well I knew that, but my site?

Once in Khartoum I spent hours riding around looking for accommodation, trying to find some places in the guide book but never did. Incidentally I have no pictures of Khartoum, for my hands were busy. After losing my patience, my hydration level and my will to look further, I took a hotel that happened to be next to where I had stopped for information/tourism. Unfortunately the man didn’t speak enough English for me to get any good answers; like where do I register(once you have entered the border of Sudan you have three days to register yourself in Khartoum), and where is a hotel to park my bike safely? So I took this room for $60US, and the man said he could register me the following day if I filled out the form and gave him a passport photo, so I’ve decided to take up his offer after reading another rider’s blog about spending half the day trying to find the registration place, and then lining up for a long time etc ….. .Once in my room I washed some clothes in the shower, and had one myself. And then I went on-line to update my blog (free fast wireless). But for some reason I wasn’t able to load my page, every time it said ‘The connection was reset’, which is not unusual really. However after I was able to visit any other site quickly, even the larger ones that I sometimes have a problem with, I still wasn’t able to access my site. So I wrote my father and asked if he could see my site in the UK and he confirmed that he could. So I did some research and learned that Sudan, China and many other countries censor sites, well I knew that, but my site?

“The Connection Has Been Reset”

China’s Great Firewall is crude, slapdash, and surprisingly easy to breach. Here’s why it’s so effective anyway.

By James Fallows

Illustration by John Ritter

Many foreigners who come to China for the Olympics will use the Internet to tell people back home what they have seen and to check what else has happened in the world.

Also see:

Interview: “Penetrating the Great Firewall”James Fallows explains how he was able to probe the taboo subject of Chinese Internet censorship. The first thing they’ll probably notice is that China’s Internet seems slow. Partly this is because of congestion in China’s internal networks, which affects domestic and international transmissions alike. Partly it is because even electrons take a detectable period of time to travel beneath the Pacific Ocean to servers in America and back again; the trip to and from Europe is even longer, because that goes through America, too. And partly it is because of the delaying cycles imposed by China’s system that monitors what people are looking for on the Internet, especially when they’re looking overseas. That’s what foreigners have heard about. They’ll likely be surprised, then, to notice that China’s Internet seems surprisingly free and uncontrolled. Can they search for information about “Tibet independence” or “Tiananmen shooting” or other terms they have heard are taboo? Probably—and they’ll be able to click right through to the controversial sites. Even if they enter the Chinese-language term for “democracy in China,” they’ll probably get results. What about Wikipedia, famously off-limits to users in China? They will probably be able to reach it. Naturally the visitors will wonder: What’s all this I’ve heard about the “Great Firewall” and China’s tight limits on the Internet? In reality, what the Olympic-era visitors will be discovering is not the absence of China’s electronic control but its new refinement—and a special Potemkin-style unfettered access that will be set up just for them, and just for the length of their stay. According to engineers I have spoken with at two tech organizations in China, the government bodies in charge of censoring the Internet have told them to get ready to unblock access from a list of specific Internet Protocol (IP) addresses—certain Internet cafés, access jacks in hotel rooms and conference centers where foreigners are expected to work or stay during the Olympic Games. (I am not giving names or identifying details of any Chinese citizens with whom I have discussed this topic, because they risk financial or criminal punishment for criticizing the system or even disclosing how it works. Also, I have not gone to Chinese government agencies for their side of the story, because the very existence of Internet controls is almost never discussed in public here, apart from vague statements about the importance of keeping online information “wholesome.”) Depending on how you look at it, the Chinese government’s attempt to rein in the Internet is crude and slapdash or ingenious and well crafted. When American technologists write about the control system, they tend to emphasize its limits. When Chinese citizens discuss it—at least with me—they tend to emphasize its strength. All of them are right, which makes the government’s approach to the Internet a nice proxy for its larger attempt to control people’s daily lives.

Disappointingly, “Great Firewall” is not really the right term for the Chinese government’s overall control strategy. China has indeed erected a firewall—a barrier to keep its Internet users from dealing easily with the outside world—but that is only one part of a larger, complex structure of monitoring and censorship. The official name for the entire approach, which is ostensibly a way to keep hackers and other rogue elements from harming Chinese Internet users, is the “Golden Shield Project.” Since that term is too creepy to bear repeating, I’ll use “the control system” for the overall strategy, which includes the “Great Firewall of China,” or GFW, as the means of screening contact with other countries. In America, the Internet was originally designed to be free of choke points, so that each packet of information could be routed quickly around any temporary obstruction. In China, the Internet came with choke points built in. Even now, virtually all Internet contact between China and the rest of the world is routed through a very small number of fiber-optic cables that enter the country at one of three points: the Beijing-Qingdao-Tianjin area in the north, where cables come in from Japan; Shanghai on the central coast, where they also come from Japan; and Guangzhou in the south, where they come from Hong Kong. (A few places in China have Internet service via satellite, but that is both expensive and slow. Other lines run across Central Asia to Russia but carry little traffic.) In late 2006, Internet users in China were reminded just how important these choke points are when a seabed earthquake near Taiwan cut some major cables serving the country. It took months before international transmissions to and from most of China regained even their pre-quake speed, such as it was. Thus Chinese authorities can easily do something that would be harder in most developed countries: physically monitor all traffic into or out of the country. They do so by installing at each of these few “international gateways” a device called a “tapper” or “network sniffer,” which can mirror every packet of data going in or out. This involves mirroring in both a figurative and a literal sense. “Mirroring” is the term for normal copying or backup operations, and in this case real though extremely small mirrors are employed. Information travels along fiber-optic cables as little pulses of light, and as these travel through the Chinese gateway routers, numerous tiny mirrors bounce reflections of them to a separate set of “Golden Shield” computers.Here the term’s creepiness is appropriate. As the other routers and servers (short for file servers, which are essentially very large-capacity computers) that make up the Internet do their best to get the packet where it’s supposed to go, China’s own surveillance computers are looking over the same information to see whether it should be stopped. The mirroring routers were first designed and supplied to the Chinese authorities by the U.S. tech firm Cisco, which is why Cisco took such heat from human-rights organizations. Cisco has always denied that it tailored its equipment to the authorities’ surveillance needs, and said it merely sold them what it would sell anyone else. The issue is now moot, since similar routers are made by companies around the world, notably including China’s own electronics giant, Huawei. The ongoing refinements are mainly in surveillance software, which the Chinese are developing themselves. Many of the surveillance engineers are thought to come from the military’s own technology institutions. Their work is good and getting better, I was told by Chinese and foreign engineers who do “oppo research” on the evolving GFW so as to design better ways to get around it. Andrew Lih, a former journalism professor and software engineer now based in Beijing (and author of the forthcoming book The Wikipedia Story), laid out for me the ways in which the GFW can keep a Chinese Internet user from finding desired material on a foreign site. In the few seconds after a user enters a request at the browser, and before something new shows up on the screen, at least four things can go wrong—or be made to go wrong. The first and bluntest is the “DNS block.” The DNS, or Domain Name System, is in effect the telephone directory of Internet sites. Each time you enter a Web address, or URL—www.yahoo.com, let’s say—the DNS looks up the IP address where the site can be found. IP addresses are numbers separated by dots—for example, TheAtlantic.com’s is 38.118.42.200. If the DNS is instructed to give back no address, or a bad address, the user can’t reach the site in question—as a phone user could not make a call if given a bad number. Typing in the URL for the BBC’s main news site often gets the no-address treatment: if you try news.bbc.co.uk, you may get a “Site not found” message on the screen. For two months in 2002, Google’s Chinese site, Google.cn, got a different kind of bad-address treatment, which shunted users to its main competitor, the dominant Chinese search engine, Baidu. Chinese academics complained that this was hampering their work. The government, which does not have to stand for reelection but still tries not to antagonize important groups needlessly, let Google.cn back online. During politically sensitive times, like last fall’s 17th Communist Party Congress, many foreign sites have been temporarily shut down this way. Next is the perilous “connect” phase. If the DNS has looked up and provided the right IP address, your computer sends a signal requesting a connection with that remote site. While your signal is going out, and as the other system is sending a reply, the surveillance computers within China are looking over your request, which has been mirrored to them. They quickly check a list of forbidden IP sites. If you’re trying to reach one on that blacklist, the Chinese international-gateway servers will interrupt the transmission by sending an Internet “Reset” command both to your computer and to the one you’re trying to reach. Reset is a perfectly routine Internet function, which is used to repair connections that have become unsynchronized. But in this case it’s equivalent to forcing the phones on each end of a conversation to hang up. Instead of the site you want, you usually see an onscreen message beginning “The connection has been reset”; sometimes instead you get “Site not found.” Annoyingly, blogs hosted by the popular system Blogspot are on this IP blacklist. For a typical Google-type search, many of the links shown on the results page are from Wikipedia or one of these main blog sites. You will see these links when you search from inside China, but if you click on them, you won’t get what you want. The third barrier comes with what Lih calls “URL keyword block.” The numerical Internet address you are trying to reach might not be on the blacklist. But if the words in its URL include forbidden terms, the connection will also be reset. (The Uniform Resource Locator is a site’s address in plain English—say, www.microsoft.com—rather than its all-numeric IP address.) The site FalunGong .com appears to have no active content, but even if it did, Internet users in China would not be able to see it. The forbidden list contains words in English, Chinese, and other languages, and is frequently revised—“like, with the name of the latest town with a coal mine disaster,” as Lih put it. Here the GFW’s programming technique is not a reset command but a “black-hole loop,” in which a request for a page is trapped in a sequence of delaying commands. These are the programming equivalent of the old saw about how to keep an idiot busy: you take a piece of paper and write “Please turn over” on each side. When the Firefox browser detects that it is in this kind of loop, it gives an error message saying: “The server is redirecting the request for this address in a way that will never complete.” The final step involves the newest and most sophisticated part of the GFW: scanning the actual contents of each page—which stories The New York Times is featuring, what a China-related blog carries in its latest update—to judge its page-by-page acceptability. This again is done with mirrors. When you reach a favorite blog or news site and ask to see particular items, the requested pages come to you—and to the surveillance system at the same time. The GFW scanner checks the content of each item against its list of forbidden terms. If it finds something it doesn’t like, it breaks the connection to the offending site and won’t let you download anything further from it. The GFW then imposes a temporary blackout on further “IP1 to IP2” attempts—that is, efforts to establish communications between the user and the offending site. Usually the first time-out is for two minutes. If the user tries to reach the site during that time, a five-minute time-out might begin. On a third try, the time-out might be 30 minutes or an hour—and so on through an escalating sequence of punishments. Users who try hard enough or often enough to reach the wrong sites might attract the attention of the authorities. At least in principle, Chinese Internet users must sign in with their real names whenever they go online, even in Internet cafés. When the surveillance system flags an IP address from which a lot of “bad” searches originate, the authorities have a good chance of knowing who is sitting at that machine. All of this adds a note of unpredictability to each attempt to get news from outside China. One day you go to the NPR site and cruise around with no problem. The next time, NPR happens to have done a feature on Tibet. The GFW immobilizes the site. If you try to refresh the page or click through to a new story, you’ll get nothing—and the time-out clock will start. This approach is considered a subtler and more refined form of censorship, since big foreign sites no longer need be blocked wholesale. In principle they’re in trouble only when they cover the wrong things. Xiao Qiang, an expert on Chinese media at the University of California at Berkeley journalism school, told me that the authorities have recently begun applying this kind of filtering in reverse. As Chinese-speaking people outside the country, perhaps academics or exiled dissidents, look for data on Chinese sites—say, public-health figures or news about a local protest—the GFW computers can monitor what they’re asking for and censor what they find. Taken together, the components of the control system share several traits. They’re constantly evolving and changing in their emphasis, as new surveillance techniques become practical and as words go on and off the sensitive list. They leave the Chinese Internet public unsure about where the off-limits line will be drawn on any given day. Andrew Lih points out that other countries that also censor Internet content—Singapore, for instance, or the United Arab Emirates—provide explanations whenever they do so. Someone who clicks on a pornographic or “anti-Islamic” site in the U.A.E. gets the following message, in Arabic and English: “We apologize the site you are attempting to visit has been blocked due to its content being inconsistent with the religious, cultural, political, and moral values of the United Arab Emirates.” In China, the connection just times out. Is it your computer’s problem? The firewall? Or maybe your local Internet provider, which has decided to do some filtering on its own? You don’t know. “The unpredictability of the firewall actually makes it more effective,” another Chinese software engineer told me. “It becomes much harder to know what the system is looking for, and you always have to be on guard.” There is one more similarity among the components of the firewall: they are all easy to thwart. As a practical matter, anyone in China who wants to get around the firewall can choose between two well-known and dependable alternatives: the proxy server and the VPN. A proxy server is a way of connecting your computer inside China with another one somewhere else—or usually to a series of foreign computers, automatically passing signals along to conceal where they really came from. You initiate a Web request, and the proxy system takes over, sending it to a computer in America or Finland or Brazil. Eventually the system finds what you want and sends it back. The main drawback is that it makes Internet operations very, very slow. But because most proxies cost nothing to install and operate, this is the favorite of students and hackers in China. A VPN, or virtual private network, is a faster, fancier, and more elegant way to achieve the same result. Essentially a VPN creates your own private, encrypted channel that runs alongside the normal Internet. From within China, a VPN connects you with an Internet server somewhere else. You pass your browsing and downloading requests to that American or Finnish or Japanese server, and it finds and sends back what you’re looking for. The GFW doesn’t stop you, because it can’t read the encrypted messages you’re sending. Every foreign business operating in China uses such a network. VPNs are freely advertised in China, so individuals can sign up, too. I use one that costs $40 per year. (An expat in China thinks: that’s a little over a dime a day. A Chinese factory worker thinks: it’s a week’s take-home pay. Even for a young academic, it’s a couple days’ work.) As a technical matter, China could crack down on the proxies and VPNs whenever it pleased. Today the policy is: if a message comes through that the surveillance system cannot read because it’s encrypted, let’s wave it on through! Obviously the system’s behavior could be reversed. But everyone I spoke with said that China could simply not afford to crack down that way. “Every bank, every foreign manufacturing company, every retailer, every software vendor needs VPNs to exist,” a Chinese professor told me. “They would have to shut down the next day if asked to send their commercial information through the regular Chinese Internet and the Great Firewall.” Closing down the free, easy-to-use proxy servers would create a milder version of the same problem. Encrypted e-mail, too, passes through the GFW without scrutiny, and users of many Web-based mail systems can establish a secure session simply by typing “https:” rather than the usual “http:” in a site’s address—for instance, https://mail.yahoo.com. To keep China in business, then, the government has to allow some exceptions to its control efforts—even knowing that many Chinese citizens will exploit the resulting loopholes.

Because the Chinese government can’t plug every gap in the Great Firewall, many American observers have concluded that its larger efforts to control electronic discussion, and the democratization and grass-roots organizing it might nurture, are ultimately doomed. A recent item on an influential American tech Web site had the headline “Chinese National Firewall Isn’t All That Effective.” In October, Wired ran a story under the headline “The Great Firewall: China’s Misguided—and Futile—Attempt to Control What Happens Online.”

Let’s not stop to discuss why the vision of democracy-through-communications-technology is so convincing to so many Americans. (Samizdat, fax machines, and the Voice of America eventually helped bring down the Soviet system. Therefore proxy servers and online chat rooms must erode the power of the Chinese state. Right?) Instead, let me emphasize how unconvincing this vision is to most people who deal with China’s system of extensive, if imperfect, Internet controls. Think again of the real importance of the Great Firewall. Does the Chinese government really care if a citizen can look up the Tiananmen Square entry on Wikipedia? Of course not. Anyone who wants that information will get it—by using a proxy server or VPN, by e-mailing to a friend overseas, even by looking at the surprisingly broad array of foreign magazines that arrive, uncensored, in Chinese public libraries. What the government cares about is making the quest for information just enough of a nuisance that people generally won’t bother. Most Chinese people, like most Americans, are interested mainly in their own country. All around them is more information about China and things Chinese than they could possibly take in. The newsstands are bulging with papers and countless glossy magazines. The bookstores are big, well stocked, and full of patrons, and so are the public libraries. Video stores, with pirated versions of anything. Lots of TV channels. And of course the Internet, where sites in Chinese and about China constantly proliferate. When this much is available inside the Great Firewall, why go to the expense and bother, or incur the possible risk, of trying to look outside? All the technology employed by the Golden Shield, all the marvelous mirrors that help build the Great Firewall—these and other modern achievements matter mainly for an old-fashioned and pre-technological reason. By making the search for external information a nuisance, they drive Chinese people back to an environment in which familiar tools of social control come into play. Chinese bloggers have learned that if they want to be read in China, they must operate within China, on the same side of the firewall as their potential audience. Sure, they could put up exactly the same information outside the Chinese mainland. But according to Rebecca MacKinnon, a former Beijing correspondent for CNN now at the Journalism and Media Studies Center of the University of Hong Kong, their readers won’t make the effort to cross the GFW and find them. “If you want to have traction in China, you have to be in China,” she told me. And being inside China means operating under the sweeping rules that govern all forms of media here: guidance from the authorities; the threat of financial ruin or time in jail; the unavoidable self-censorship as the cost of defiance sinks in. Most blogs in China are hosted by big Internet companies. Those companies know that the government will hold them responsible if a blogger says something bad. Thus the companies, for their own survival, are dragooned into service as auxiliary censors. Large teams of paid government censors delete offensive comments and warn errant bloggers. (No official figures are available, but the censor workforce is widely assumed to number in the tens of thousands.) Members of the public at large are encouraged to speak up when they see subversive material. The propaganda ministries send out frequent instructions about what can and cannot be discussed. In October, the group Reporters Without Borders, based in Paris, released an astonishing report by a Chinese Internet technician writing under the pseudonym “Mr. Tao.” He collected dozens of the messages he and other Internet operators had received from the central government. Here is just one, from the summer of 2006:

17 June 2006, 18:35From: Chen Hua, deputy director of the Beijing Internet Information Administrative BureauDear colleagues, the Internet has of late been full of articles and messages about the death of a Shenzhen engineer, Hu Xinyu, as a result of overwork. All sites must stop posting articles on this subject, those that have already been posted about it must be removed from the site and, finally, forums and blogs must withdraw all articles and messages about this case.

“Domestic censorship is the real issue, and it is about social control, human surveillance, peer pressure, and self-censorship,” Xiao Qiang of Berkeley says. Last fall, a team of computer scientists from the University of California at Davis and the University of New Mexico published an exhaustive technical analysis of the GFW’s operation and of the ways it could be foiled. But they stressed a nontechnical factor: “The presence of censorship, even if easy to evade, promotes self-censorship.” It would be wrong to portray China as a tightly buttoned mind-control state. It is too wide-open in too many ways for that. “Most people in China feel freer than any Chinese people have been in the country’s history, ever,” a Chinese software engineer who earned a doctorate in the United States told me. “There has never been a space for any kind of discussion before, and the government is clever about continuing to expand space for anything that doesn’t threaten its survival.” But it would also be wrong to ignore the cumulative effect of topics people are not allowed to discuss. “Whether or not Americans supported George W. Bush, they could not avoid learning about Abu Ghraib,” Rebecca MacKinnon says. In China, “the controls mean that whole topics inconvenient for the regime simply don’t exist in public discussion.” Most Chinese people remain wholly unaware of internationally noticed issues like, for instance, the controversy over the Three Gorges Dam. Countless questions about today’s China boil down to: How long can this go on? How long can the industrial growth continue before the natural environment is destroyed? How long can the super-rich get richer, without the poor getting mad? And so on through a familiar list. The Great Firewall poses the question in another form: How long can the regime control what people are allowed to know, without the people caring enough to object? On current evidence, for quite a while. So far all I can think of is that the man I met in the pouring rain at the gas station who was very outward and gregarious, might have been there to do exactly as he did; ingratiate himself, take a picture of me, and get my email and website. Argggh, I want to get to Europe. The thing is, I came here not expecting anything and enter every country without judgment, regardless of what people tell me before I come or go, for I came on this journey to learn. Personally I don’t mind what people believe whether it be Catholicism, Buddhism, or Muslim, but what I don’t like is being lied to. If someone asks me how I feel I tell them how I feel. But to be manipulated and coerced into some sort of governmental paranoia, well, all I can say is the one who is manipulative and deceitful is the one who fears. This is not a way to grow and to expand one’s beliefs, or to encourage others to follow and join the group, which is what I understand most religions to desire. So, I sit here in the hotel room in Khartoum, not wanting to explore at all. I don’t feel like taking pictures and I just want to leave. Why even allow tourists into the country is a wonder to me, if all they want is your money at the entry and exit and for you to leave within the two week period provided? Such a shame …. On a lighter note, they are shooting some scenes from a TV series in the lobby, then the restaurant, then some rooms … and yes they are working nights.  Check out the boom pole, a shotgun mic dressed in full wind protection with a four foot broom stick, inside the building. It reminds me of my entry into the film business for $50/day; plug this in, move that lamp over there, push the dolly, drive that camper, help them with their make-up, and hold this microphone. I never knew I’d be swinging the pole for the next twenty years, although I must admit, I’m happy I have.

Check out the boom pole, a shotgun mic dressed in full wind protection with a four foot broom stick, inside the building. It reminds me of my entry into the film business for $50/day; plug this in, move that lamp over there, push the dolly, drive that camper, help them with their make-up, and hold this microphone. I never knew I’d be swinging the pole for the next twenty years, although I must admit, I’m happy I have.  Later I watched the first night of Ramadan on TV, from the Mecca in Saudi Arabia. It was great because they translated the prayers in English, and I was better able to understand the Muslim religion, and the rules for such faith.

Later I watched the first night of Ramadan on TV, from the Mecca in Saudi Arabia. It was great because they translated the prayers in English, and I was better able to understand the Muslim religion, and the rules for such faith.

There’s always one guy who bows later than everyone else ….

There’s always one guy who bows later than everyone else …. (sorry for the past and present tense, can’t be bothered to re-write) Anyway, I am preparing for the long hot ride to Dongola early tomorrow morning. I have been told by the nice manager here at the Dubai Hotel, who is taking care of my registration here in Khartoum, that there is a nice ancient ruin to see near his home town. I don’t have the time on my visa to visit Meroe, the famous pyramids of Sudan, but he says I will like very much the ruins he told me about near Dongola. He also told me it was possible to get fuel (benzene) during the desert ride to Dongola as there is a stretch on my map of some 350 kilometers without a village. Regardless I have collected three 1.5 litre water bottles to fill with petrol on my way out of Khartoum, for I don’t want to be stuck in the middle of the hot asphalt for any reason I can prevent. I’ve also loaded up on water due to my recent two tyre punctures, thinking of preventative measures for a number of possible scenarios. (heavy sigh) …. I’m so disappointed that my simple site has been censored, and for what, because I told that man when he asked me, ‘I don’t believe in God, I believe that the People are God, and nobody will help the People except the People … but faith is another thing and for others to choose’. He caught me at a bad time; tired, cold, hungry and soaked to the bone. But for the record, I wasn’t the one who broke the rule of any religion, not to lie and be deceitful for one’s own gain.I have to admit I often feel that I am very alone, and that the only reason anyone talks to me is because they want my money. And then I meet a man like Tarig who is the manager of this hotel. He is so sincere and has the most honest chuckle I have heard in a long time. Not only did he help me with my registration, he also gave me the best rate in Khartoum for my US dollars, found me a Sudan sticker for my bike, and when paying my bill tonight he asked if I had enough money, and if I wanted he would give me some and that I could send it back to him from Canada when I returned home. Later on I went down to order a little food and the restaurant was packed with people eating from a buffet. Today is the first day of Ramadan, and everyone had fasted all day until now, 7:30pm. So everyone was feverishly eating, while I was standing there looking at everyone a woman with her friends said in English, ‘Welcome’. ‘Thank you’, I answered and then one of the staff said in Arabic and sign language, ‘Please eat’. ‘How much is it’ I gestured? ‘Nothing, please’. So its times like these that I feel human again, that no one is trying to get anything from me, and that I am truly welcome.

(sorry for the past and present tense, can’t be bothered to re-write) Anyway, I am preparing for the long hot ride to Dongola early tomorrow morning. I have been told by the nice manager here at the Dubai Hotel, who is taking care of my registration here in Khartoum, that there is a nice ancient ruin to see near his home town. I don’t have the time on my visa to visit Meroe, the famous pyramids of Sudan, but he says I will like very much the ruins he told me about near Dongola. He also told me it was possible to get fuel (benzene) during the desert ride to Dongola as there is a stretch on my map of some 350 kilometers without a village. Regardless I have collected three 1.5 litre water bottles to fill with petrol on my way out of Khartoum, for I don’t want to be stuck in the middle of the hot asphalt for any reason I can prevent. I’ve also loaded up on water due to my recent two tyre punctures, thinking of preventative measures for a number of possible scenarios. (heavy sigh) …. I’m so disappointed that my simple site has been censored, and for what, because I told that man when he asked me, ‘I don’t believe in God, I believe that the People are God, and nobody will help the People except the People … but faith is another thing and for others to choose’. He caught me at a bad time; tired, cold, hungry and soaked to the bone. But for the record, I wasn’t the one who broke the rule of any religion, not to lie and be deceitful for one’s own gain.I have to admit I often feel that I am very alone, and that the only reason anyone talks to me is because they want my money. And then I meet a man like Tarig who is the manager of this hotel. He is so sincere and has the most honest chuckle I have heard in a long time. Not only did he help me with my registration, he also gave me the best rate in Khartoum for my US dollars, found me a Sudan sticker for my bike, and when paying my bill tonight he asked if I had enough money, and if I wanted he would give me some and that I could send it back to him from Canada when I returned home. Later on I went down to order a little food and the restaurant was packed with people eating from a buffet. Today is the first day of Ramadan, and everyone had fasted all day until now, 7:30pm. So everyone was feverishly eating, while I was standing there looking at everyone a woman with her friends said in English, ‘Welcome’. ‘Thank you’, I answered and then one of the staff said in Arabic and sign language, ‘Please eat’. ‘How much is it’ I gestured? ‘Nothing, please’. So its times like these that I feel human again, that no one is trying to get anything from me, and that I am truly welcome. After leaving Khartoum at 6am, I rode in a sand storm for most of the day …

After leaving Khartoum at 6am, I rode in a sand storm for most of the day …

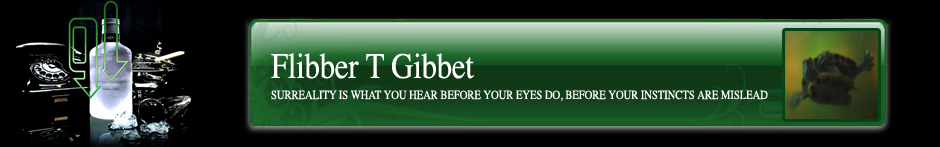

… before I reached the laid back town of Dongola. I stopped for a smoke under a tree after taking a quick look around town, to decide how to go about finding a hotel since every sign was in Arabic. I later stopped at a pharmacy, surely someone there will speak English as they had to have had to go to University to become a pharmacist. And sure enough one of the people took me to a nice hotel, with AC, a fan and satellite TV with four English movie channels. But before being allowed to check into the hotel I had to first register with the police station, to ask permission to stay in Dongola.

… before I reached the laid back town of Dongola. I stopped for a smoke under a tree after taking a quick look around town, to decide how to go about finding a hotel since every sign was in Arabic. I later stopped at a pharmacy, surely someone there will speak English as they had to have had to go to University to become a pharmacist. And sure enough one of the people took me to a nice hotel, with AC, a fan and satellite TV with four English movie channels. But before being allowed to check into the hotel I had to first register with the police station, to ask permission to stay in Dongola.  So I just hung out in the room watching some really good movies until falling asleep. The next morning I went about finding some oil to do a change, and to do some other maintenance on the bike, before retiring to my room for the hottest part of the day. Oh what luxury to be cool and to watch English TV. Later in the evening I went across the street for some snacks and met U3, a University teacher/shop keeper. He spoke very good English so we chatted for quite some time before I went back to my room with Goat’s cheese, olives, figs, crackers, water and pop. Q3 invited me for ‘Break Fast’ at 7:30pm, so I showed up at 8pm thinking it will give he and his friends time to fill up before I arrived as they hadn’t eaten all day, but when I got there the food was gone and Q3 said, ‘I invited you for Break Fast and you did not come’. ‘I will come early tomorrow for sure’ I said.

So I just hung out in the room watching some really good movies until falling asleep. The next morning I went about finding some oil to do a change, and to do some other maintenance on the bike, before retiring to my room for the hottest part of the day. Oh what luxury to be cool and to watch English TV. Later in the evening I went across the street for some snacks and met U3, a University teacher/shop keeper. He spoke very good English so we chatted for quite some time before I went back to my room with Goat’s cheese, olives, figs, crackers, water and pop. Q3 invited me for ‘Break Fast’ at 7:30pm, so I showed up at 8pm thinking it will give he and his friends time to fill up before I arrived as they hadn’t eaten all day, but when I got there the food was gone and Q3 said, ‘I invited you for Break Fast and you did not come’. ‘I will come early tomorrow for sure’ I said.

The next day I went to the market for supplies, and while doing so I saw two bikers parked in front of some shops. My feeling at the time was they were busy, or knew what they were doing, or not too social at the moment, or maybe it was me. Anyway I looked at them as they looked at me and then I just kept on with my shopping for razors, water, smokes and food. I figured I would see them around town sooner or later anyway. At 7pm I went down to Q3’s shop to have a chat, and to eat Break Fast with he and his friends. When the call was made over the loud speaker from the nearby Mosque to begin eating, well it was all gone in seconds. I didn’t have the heart to eat from the main dish that was being devoured quickly, and also didn’t want to insult Q3 so I nibbled from the other dishes that also quickly disappeared. I think everything was gone in 10 minutes. So after we had coffee, they sat down on their mats to pray, so I joined them facing east, bowing and thinking of no one in particular, but just happy to be here with these welcoming people. After more discussions about this and that, Q3 and I said our good-bye’s and I retired to my room for one last night of air conditioned, Break Fast in bed TV night.

The next day I went to the market for supplies, and while doing so I saw two bikers parked in front of some shops. My feeling at the time was they were busy, or knew what they were doing, or not too social at the moment, or maybe it was me. Anyway I looked at them as they looked at me and then I just kept on with my shopping for razors, water, smokes and food. I figured I would see them around town sooner or later anyway. At 7pm I went down to Q3’s shop to have a chat, and to eat Break Fast with he and his friends. When the call was made over the loud speaker from the nearby Mosque to begin eating, well it was all gone in seconds. I didn’t have the heart to eat from the main dish that was being devoured quickly, and also didn’t want to insult Q3 so I nibbled from the other dishes that also quickly disappeared. I think everything was gone in 10 minutes. So after we had coffee, they sat down on their mats to pray, so I joined them facing east, bowing and thinking of no one in particular, but just happy to be here with these welcoming people. After more discussions about this and that, Q3 and I said our good-bye’s and I retired to my room for one last night of air conditioned, Break Fast in bed TV night.  The next morning I was off, an hour late. I wanted to leave at 7am but ended up leaving at 8am. Q3 was going to ask his sister to wave to me from the side of the road at the next town to enjoy a cup of tea, but I did not see her, probably because I was late, nor did I see the road to the ruins I was supposed to visit, so I just kept on going to try and beat the heat of the day, continuing on to Wadi Halfa, the border town ferry ride to Aswan, Egypt.

The next morning I was off, an hour late. I wanted to leave at 7am but ended up leaving at 8am. Q3 was going to ask his sister to wave to me from the side of the road at the next town to enjoy a cup of tea, but I did not see her, probably because I was late, nor did I see the road to the ruins I was supposed to visit, so I just kept on going to try and beat the heat of the day, continuing on to Wadi Halfa, the border town ferry ride to Aswan, Egypt.

There is fuel along the way, one just has to go into the villages to ask around.

There is fuel along the way, one just has to go into the villages to ask around.

As I pulled into Wadi I waved to a white guy who was walking around, so I pulled over and met Dale from South Africa. I had seen Dale and his friend Rui(Roy) the day before in Dongola, wearing their riding gear standing beside their bikes but for some reason I didn’t go over to speak to them and as I later learned, they also did not call to me. It’s too bad really because they were looking for a good place to stay and I could have suggested they stay at my hotel. In the end they rode 100 km’s north and camped beside the Nile, sleeping with an unbearable heat and short on water. So anyway, I met Dale and he pointed to where they were staying, and then I met Rui.

As I pulled into Wadi I waved to a white guy who was walking around, so I pulled over and met Dale from South Africa. I had seen Dale and his friend Rui(Roy) the day before in Dongola, wearing their riding gear standing beside their bikes but for some reason I didn’t go over to speak to them and as I later learned, they also did not call to me. It’s too bad really because they were looking for a good place to stay and I could have suggested they stay at my hotel. In the end they rode 100 km’s north and camped beside the Nile, sleeping with an unbearable heat and short on water. So anyway, I met Dale and he pointed to where they were staying, and then I met Rui.  We met with Magdi’s cousin Mazir, both family fixer’s, to organize the paper work for the ferry, and then ate dinner together talking about this that and the other things, until retiring to our respective rooms, as hot and airless as they were. We ended up pulling the beds out into the passage way outside of the rooms, for it carried a nice breeze; the rooms only becoming locker rooms for our stuff.

We met with Magdi’s cousin Mazir, both family fixer’s, to organize the paper work for the ferry, and then ate dinner together talking about this that and the other things, until retiring to our respective rooms, as hot and airless as they were. We ended up pulling the beds out into the passage way outside of the rooms, for it carried a nice breeze; the rooms only becoming locker rooms for our stuff.

The next day while we were heading out of our accommodation for morning tea, Dale spotted two cars(trucks) one with a South African license plate. He asked if it was okay to stop and visit with them and of course I said yeah, and then I realized it was Rudy and Andreas, the two men I met in Nairobi at the Jungle Junction waiting for their Ethiopian visas. It was great to see them again, and now our posse had grown to five people, three bikes and two cars.We spent the long hours with nothing to do except talking about this and that, drinking tea and dreaming of AC and beer. One evening we had the pleasure of sharing dinner with a Spanish woman named Olga, who was a free spirit, choosing to travel alone for her friends as she said, both men and women, were too tidy and too used to everything just as it was. I think we all privately thought, ‘If only we were going the same way’. The next day we had something to do besides hide from the heat, to load our vehicles onto the barge heading for Aswan, Egypt. Magdi and Masir are fantastic fixers, and everything was flawless. Everyone knows them so I need not put their info here, for they will find you anyway.

The next day while we were heading out of our accommodation for morning tea, Dale spotted two cars(trucks) one with a South African license plate. He asked if it was okay to stop and visit with them and of course I said yeah, and then I realized it was Rudy and Andreas, the two men I met in Nairobi at the Jungle Junction waiting for their Ethiopian visas. It was great to see them again, and now our posse had grown to five people, three bikes and two cars.We spent the long hours with nothing to do except talking about this and that, drinking tea and dreaming of AC and beer. One evening we had the pleasure of sharing dinner with a Spanish woman named Olga, who was a free spirit, choosing to travel alone for her friends as she said, both men and women, were too tidy and too used to everything just as it was. I think we all privately thought, ‘If only we were going the same way’. The next day we had something to do besides hide from the heat, to load our vehicles onto the barge heading for Aswan, Egypt. Magdi and Masir are fantastic fixers, and everything was flawless. Everyone knows them so I need not put their info here, for they will find you anyway.

Just to kill some time, I did a malaria check with one of the three kits I had, and found I was negative.

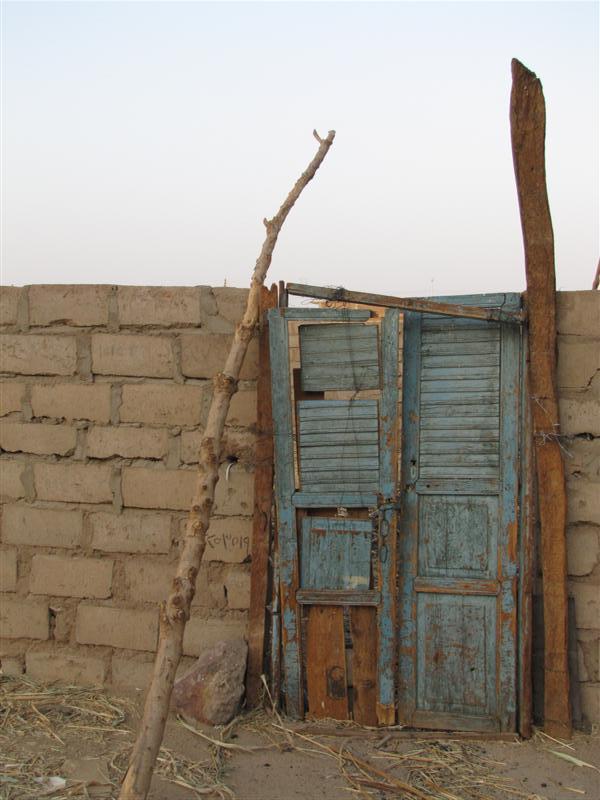

Just to kill some time, I did a malaria check with one of the three kits I had, and found I was negative. On our last night in Wadi Halfa, I went to the Egyptian restaurant we had been frequenting, for a tea outside of the restaurant, from the ladies who pour such delights on the street, with a touch of spearmint within such delicious chai tea; the Egyptian daughters in my mind, from the father of four with wife making a buck in between the years of life, I found myself doing neither, except climbing the small rock mountain above the centre of Wadi Halfa, to have a good look at this desert border town, wondering about this and that.

On our last night in Wadi Halfa, I went to the Egyptian restaurant we had been frequenting, for a tea outside of the restaurant, from the ladies who pour such delights on the street, with a touch of spearmint within such delicious chai tea; the Egyptian daughters in my mind, from the father of four with wife making a buck in between the years of life, I found myself doing neither, except climbing the small rock mountain above the centre of Wadi Halfa, to have a good look at this desert border town, wondering about this and that.

And just in the middle of my revelry, two Korean lads came climbing up to my solstice. At first I thought, how can you be so bold to interfere with my privacy, but then I remembered, how keen and curious the Asians seem to be so confidently and without fuss. After about twenty minutes of these two students taking pictures of themselves behind me, I asked one of them to take my picture adding I wasn’t going to move from my position, and for him just to take the picture how he sees it. A moment later he said he took two, and that I should choose. I answered that I didn’t care and didn’t look, for I trusted his taste anyway. It’s a true picture I believe….

And just in the middle of my revelry, two Korean lads came climbing up to my solstice. At first I thought, how can you be so bold to interfere with my privacy, but then I remembered, how keen and curious the Asians seem to be so confidently and without fuss. After about twenty minutes of these two students taking pictures of themselves behind me, I asked one of them to take my picture adding I wasn’t going to move from my position, and for him just to take the picture how he sees it. A moment later he said he took two, and that I should choose. I answered that I didn’t care and didn’t look, for I trusted his taste anyway. It’s a true picture I believe….

A little later Andreas and Dale climbed up the mountain too, for who can say how tall a mountain can be? It was then I decided to climb down, and get myself that delicious cup of tea.

A little later Andreas and Dale climbed up the mountain too, for who can say how tall a mountain can be? It was then I decided to climb down, and get myself that delicious cup of tea.

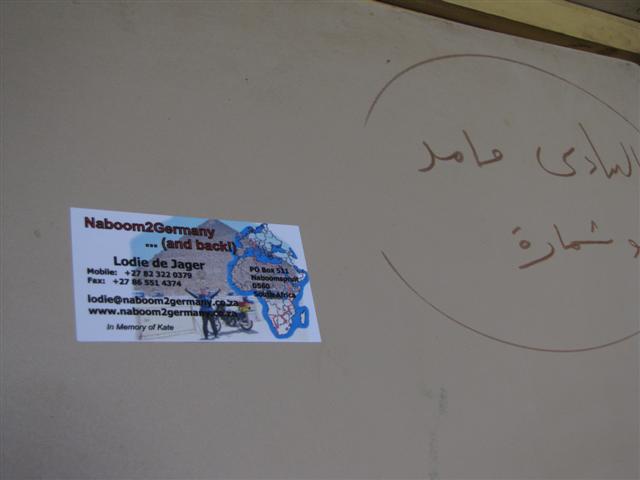

The next day on the ferry, I was lead to my room by Masir, later finding Loudie’s travel card, the biker I met also at the Jungle Junction, stuck on the inside of my cabin door, number 21. It took some time before we set off, and to be honest I was content just to sit aboard a boat that had yet to sail, satisfied with the idea of moving on, even though we hadn’t blown a bit.

The next day on the ferry, I was lead to my room by Masir, later finding Loudie’s travel card, the biker I met also at the Jungle Junction, stuck on the inside of my cabin door, number 21. It took some time before we set off, and to be honest I was content just to sit aboard a boat that had yet to sail, satisfied with the idea of moving on, even though we hadn’t blown a bit.

Just before we left the dock, Masir wanted to move the passenger I was sharing a room with for another guy in Rudy’s cabin, who happened to be suffering from some sort of illness, so that Rudy and I could share a cabin together instead. His words were, ‘The people in Wadi Halfa complained of the Jewish man’s incessant praying into the corners of the room, while rocking back and forth. In the end, we did not swap rooms, and in the end, I got to observe the prayers of a faithful Jewish man, leather straps included, and as far as I can tell from the advice of Rui, a way of hurting oneself to concentrate within the faith. Personally, I do not know, I am only an observer of such things.

Just before we left the dock, Masir wanted to move the passenger I was sharing a room with for another guy in Rudy’s cabin, who happened to be suffering from some sort of illness, so that Rudy and I could share a cabin together instead. His words were, ‘The people in Wadi Halfa complained of the Jewish man’s incessant praying into the corners of the room, while rocking back and forth. In the end, we did not swap rooms, and in the end, I got to observe the prayers of a faithful Jewish man, leather straps included, and as far as I can tell from the advice of Rui, a way of hurting oneself to concentrate within the faith. Personally, I do not know, I am only an observer of such things.

Excerpt from journal …. Day 427 Wadi Halfa to Aswan …. Today we get to leave this quiet simple town … I just can’t/don’t understand how people can live here with nothing to do, not even to grow their own food or raise animals even though they do, nothing is all I see. I am excited to get out of the heat, the boredom, and the prohibition. The ferry ride was pleasant and dirty. I shared with a faithful Jewish man, for he did not mind praying in the room with me, his faith without paranoia while I was there, in fact he invited me even though I left the room, and yet he stuffed a Kleenex in the key hole of the door just in case someone else should see. At one point I asked him why he kept looking out the door every few seconds, to cure his disbelief while I read my book, and he answered that he was waiting for the bathroom to become free, even though I pointed out that he was looking at the woman’s washroom. I believe he was uncomfortable with practicing his religion among the Muslim’s. For me I don’t care, and wonder why so many people do.

AN ADDITION TO THIS SECTION DONE FROM ENGLAND ….

I know this part doesn’t belong in the England section but if I put in the Egypt section most of you won’t see it anyway. Today I wrote Rui on FB to wish him a happy birthday, and to say let’s meet for a beer in Wadi Halfa (which of course is not possible with no alcohol there), and he said sure see you in 15 minutes, and then he added, I’ll line up the Egyptian ladies. I had completely forgotten about this part of the trip, and that Rui had sent me some pictures a while back to show me what it was like while the Egyptian father of three daughters and wife, living in Wadi Halfa with at least two restaurants, they originally from Alexandria, there just for two years to make the money and run, well this conversation you will see was quite something. First though, are some other pictures that Dale took with Rui’s camera, which is really exciting to receive pictures from other cameras for another view than your own. That’s the fixer(Masir or Magdi) in Wadi that you will meet if you are taking the boat to Egypt, or vice versa.

Olga from Barcelona, who I missed by two days when I was there. She was travelling alone and heading for Ethiopia. And of course Rudi and Andreas

When the father and I were talking he was asking me questions about Canada, and what I did for a living and things like that until suddenly he was asking me how much money it would cost to pay me to sponsor him and his family to move to Canada, suggesting casually by describing his three daughters with one word each, something like, she work hard, she trouble, she getting married. When I had realized how the conversation had shifted due to my ignorance, I was suddenly shocked, and when all was done, Rui was grinning ear to ear saying he got it all on camera.

Rui and I discussing our difficult situation upon arrival in Aswan, Egypt, having two fixers, and one pissed off Egyptian Customs Officer who wanted his fixer to be first, while Rudi was still being contained by police on the boat from Wadi Halfa.

And then the Wadi Halfa gang having a cold beer by the pool in Aswan. Miss you fellas. Rudi and Andreas where are you now?